I’m writing this article because the existing literature I can find (the wikipedia article about STANAG 4694, and some associated presentations on the NATO website) don’t provide detail into the rationale for the change; I think we can infer some rationale for the changes. Additionally, the articles in the gun media that I can find don’t seem to understand the changes, beyond the cursory summary given on the NATO website. The datum schemes for MIL-STD-1913 and STANAG 4694 are also very novel; these sorts of datum schemes are not often seen in GD&T textbooks. Finally, we can also see how STANAG 4694 incorporates obsolescent features to maintain compatibility with the “legacy” MIL-STD-1913 rails.

THE MIL-STD-1913 "PICATINNY" RAIL

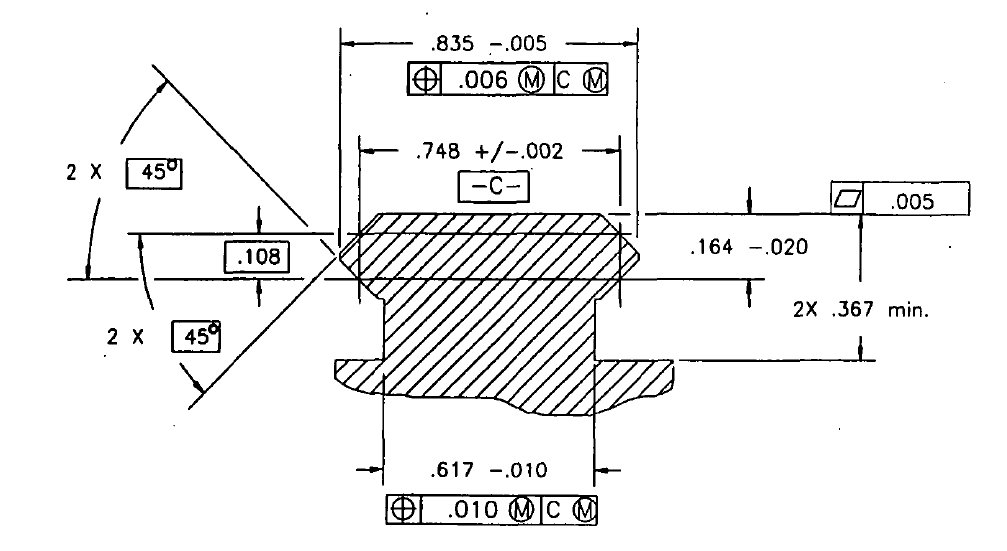

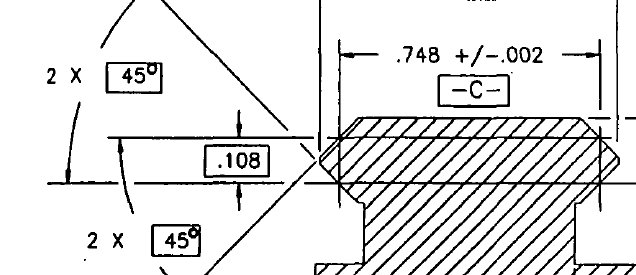

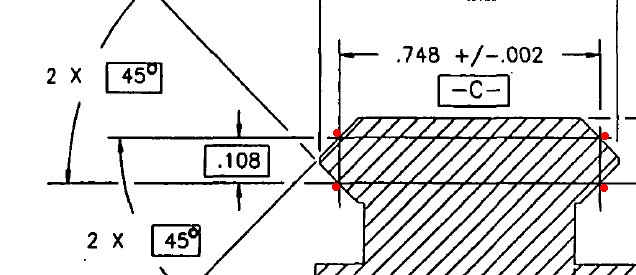

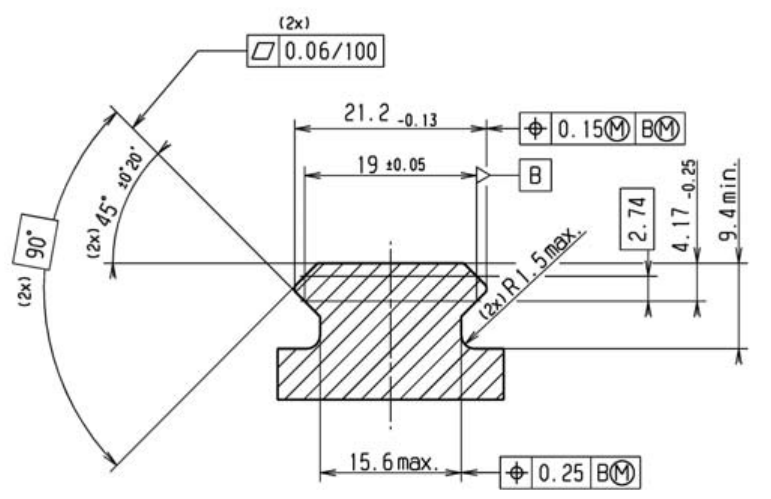

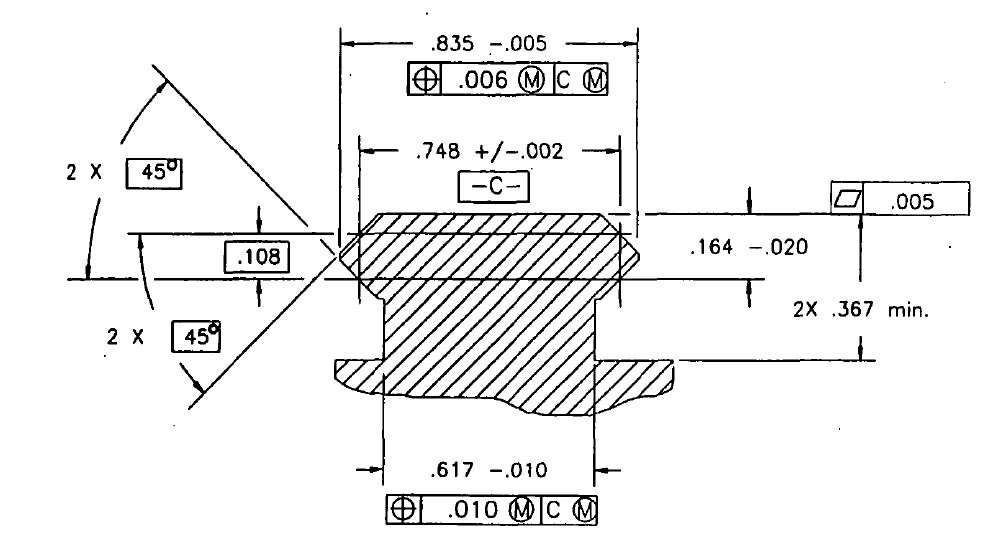

Let’s start with the mathematical description of Datum C

On a drawing, Datums are how interfaces are defined. For the Picatinny Rail, the Datum is what is theoretically the interface between the Rail itself and the sights.

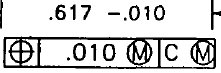

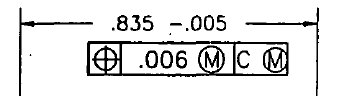

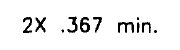

Let’s work our way through the clearance dimensions:

This total potential width used (.627) is called the Virtual Condition, which is a very important concept in GD&T. Functionally, this means that we can know the maximum space that the base can take up, so we can design a rail grabber that doesn’t interfere with it. Datum C is referenced at Max Material Boundary (MMB), which means that as the features that comprise Datum C depart from their Max Material Boundary (as the beveled surfaces of the rail shrink inward from their max size) the bottom can shift as well; this is called “Datum Feature Shift”, and it is not quite the same thing as Bonus tolerance, though it has somewhat similar effects. Datum Feature Shift might be best explained as allowing the feature to rattle around as the Datum Feature shrinks; if your foot shrinks, then your shoe can move around on your foot before your toes are crushed.

mounts to use the mil-std-1913 "picatinny" rail

How does this differ from the mathematically ideal mount?

There are some problems here though. Since the four beveled surfaces aren't controlled as far as their angles, the contact locations for any given side will shift closer together as the angles decrease, and farther apart as the angles increase. The magnitude of this shift will be proportional to the radius of the rollers. We can minimize this shift by decreasing the rollers' radii, but this will increase Hertzian contact stress (the limit here would be a sharp edge, which has theoretically infinite stress prior to the rail surface being dented/damaged). A narrow radius also allows for possible damage of the mount, which will make all this mathematical perfection irrelevant anyway. (For comparison here, think about how hard it is to put a dent into a trailer hitch ball, compared to trying to nick the edge of a knife).

So while we can imagine a mount that would be mathematically ideal for attaching to a Picatinny rail, we can't build one that will work well in practice. It's much easier to define a datum mathematically than it is to physically interact with one; this is a hard-learned lesson for most GD&T users.

Why does a mathematically ideal mount matter?

1 MOA shift means what over a 4-inch long rail? Tangent of 1/60 deg (1 MOA) is 0.00029, meaning 1MOA shift equates to .0012 inch shift over 4 inches (.00029 x .4). That's one third the thickness of a sheet of printer paper (.003-.005 thick). This means that it takes very little change to move the point of impact when removing and reinstalling a scope.

To make sure the scope goes on the same way every time, we can can do many different things.

We can make sure that the scope mount grabs the rail with the same force in the same way every time. As the scope mount grabs the rail, it will bend slightly. (The rail itself will crush inward ever so slightly as well, but that effect is very minor in comparison.) If we can make sure that the mount grabs the rail with the same force every time, we can make sure the scope mount bends the same way every time, and the scope will be in the same place relative to the rail. Springs can help with this (like the Bobro mount), as can adjustment (like the LaRue mount), or consistent torque on mounting screws (most screw mounts, also the Aimpoint mount with the torque nob).

We can also make sure that the scope mount attaches to the rail in the same spot every time. The rail will be pretty similar in cross-section at different points, but it won't be exactly the same. This means that our methods above of getting the same force will be hindered somewhat, because our adjustment methods won't work as well. The elastic in a fat guy's sweatpants will grab him about the same within certain waistline limits, but it won't work as well if the fat guy loses a lot of weight. (It should also be pointed out that the rails' straightness tolerances are usually such that zero will be lost just by moving the mount forward on the rail.)

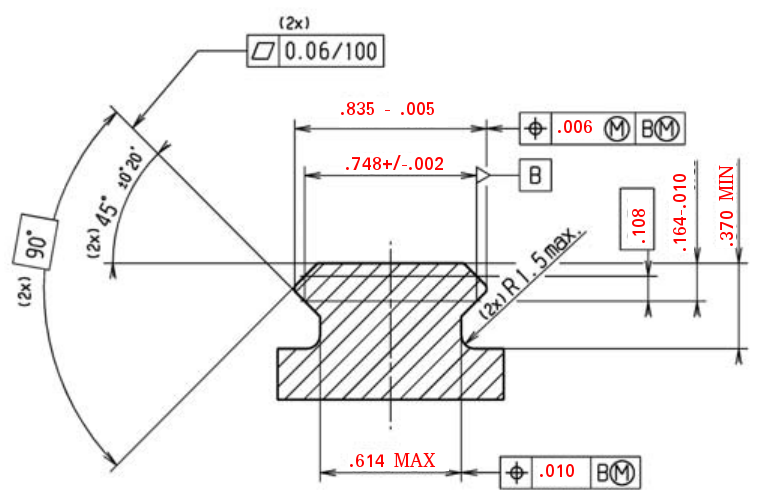

The NATO Rail (STANAG 4694)

The other major change is that the distance from the bottom pair of contact points (on the bottom angled surface) to the top face now has a tighter tolerance. It used to be +000 / -.020, but now it’s +.000 / - .010, which is half of the tolerance. The bottom angled surfaces now also have their own form tolerance (flatness .003 / 4.000), which was not present on the Picatinny spec.

The top surface no longer has explicit form control (the Picatinny spec has flatness .005), but the distance from the bottom angled surface contact up to the top face has a much tighter tolerance, so I'll argue that the NATO rail is tighter nonetheless.

Most of the clearance dimensions are the same. The width of the outer edges of the rail is identical. The clearance from the top surface of the rail to the bottom of the base has increased by .003, which is backward compatible (since it will allow all Picatinny mounts, and then some), but is also so close as to be meaningless in practice (.003 is the width of a sheet of paper). The actual width and virtual condition of the base is functionally very similar; .010 position tolerance, with datum feature shift. The difference is that the Picatinny rail is positioned at MMC, and thus has bonus tolerance available as the width of the base shrinks (creating more clearance); the NATO rail has no minimum width of the base (which also creates more clearance). Minimal practical difference, as I suspect that most NATO rails will be manufactured with much more clearance than would be allowed by the Picatinny spec.

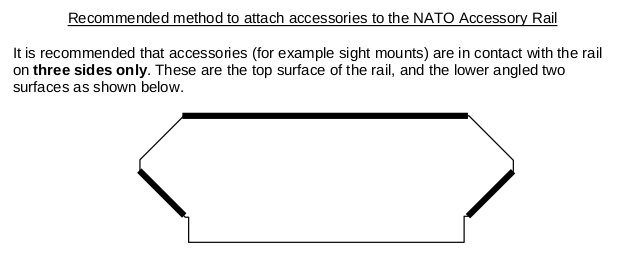

Specifying the “Preferred” mounting arrangement

This is the mounting arrangement most commonly used anyway, so the practical effects of this change are pretty minimal.

This mounting arrangement does tie in with the changes to the dimensioning. The underside bevels now have form control, which is good as there will be more consistency in what the grabbers will see. The distance from the tangent points on the underside bevels to the top surface is now much tighter; for mounts that touch the top surface and the underside bevels, they'll be much more consistent. It should be mentioned that the preferred mounting arrangement doesn't involve the topside bevels at all; they're still present mainly for backward compatibility with “correct” MIL-STD-1913 mounts, as rare as they are.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed